I promised you another post about my inspiration for The Wolf & the Witch, but things got away from me. The last two months have been hectic, but I’m catching up.

In The Wolf & the Witch, the father of the heroine, Alys, was Robert Armstrong. He died when she was a child (no spoilers from me!) but had a reputation as a man who had made a deal with a demon. She reveals that he had lost a great deal before he died himself: her mother had died in childbirth, so he was a widower; he had made some poor decisions in administering his holding and household, so had no servants or villeins any longer; he had been robbed of all his wealth and his treasury was empty; and finally, he was reputed to have made a deal with a demon of the classic one-soul-for unlimited-power variety. (Why he would have been in such dire straits after making such a deal is another question altogether.) The ruin of Kilderrick is said to be haunted by a redcap goblin, which was Robert’s familiar – a detail that Alys uses to advantage to keep intruders away. In the course of the story, Alys realizes a few key truths about her father.

But the point of this post is to share my inspiration for Robert, which was William II de Soules. (I’ve already posted about Hermitage Castle being the inspiration for fictional Kilderrick.) William was a nobleman in the fourteenth century who held Hermitage castle and died in 1321. Like the fictional Robert, William had a considerable reputation, not all of which was true.

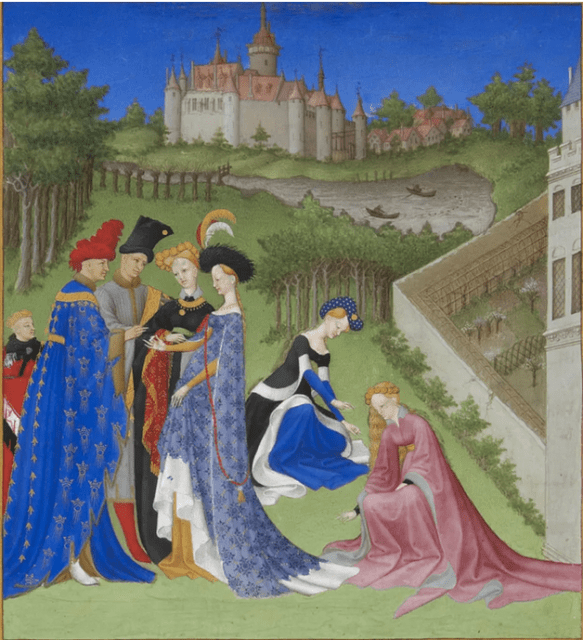

Let’s go back a bit. The first William de Soules was a Scottish nobleman granted the holding of Liddesdale by the Scottish king, and Butler of Scotland. His son, Nicholas de Soules, inherited the holding and the titles upon his father’s death around ???. When Margaret, the Maid of Norway, died in 1290, Nicholas was one of the contenders for the Scottish crown—the story was that his grandmother had been an illegitimate daughter of King Alexander II. His quest for the throne did not succeed and in 1296, he pledged homage to Edward I of England. He and his wife, Margaret Comyn, had two sons, William and John.

Nicholas’ son, William (II), was received into the peace of England by Edward I in 1304. He remained in the service of the English until Robert the Bruce’s victory at Bannockburn in 1314—then he changed his allegiance back to Scotland. He became Butler of Scotland, like his father and grandfather, but then, in 1320, was part of a plot challenging Robert the Bruce. It seems likely that the old idea of the de Soules line having a claim to the throne might have been behind this. The plot was found out and William arrested at Berwick. He confessed to his treason at the Black Parliament of 1320, but the king spared his life, making his considerable lands forfeit instead. William was imprisoned in Dumbarton Castle, where he died in 1321, leaving a daughter and heiress, Ermengarde.

The rumors about William are far more interesting! He was reputed to be a sorceror, tutored by the famous (dead) magician, Michael Scot. William could not be bound with ropes, injured by steel or killed by ordinary means because of his powers. He was large and cruel, seizing children for his blood rites and terrorizing both his vassals and his neighbors. He was said to have fortified his fortress, Hermitage Castle, against the king using supernatural means. (Even so, it wasn’t the castle that we recognize on that site: the castle that survives is a remnant of the fortification build by the Earl of Douglas after the holding was forfeited by Soules.) William’s abused vassals complained repeatedly to the king, Robert the Bruce, who is dismissive of their concerns in these stories, telling them “Boil him, if you please, but let me hear no more of him.”

And so, they do. The villagers have a chain forged to restrain the large and powerful William. He is taken forcibly to the Ninestang Ring and boiling him in molten lead. The story continues that Hermitage Castle sank into the ground after the passing of its lord, and that the keep is haunted still by William’s familiar, Robin Redcap.

There is a ballad about William called Lord Soulis composed by J. Leyden and included by Sir Walter Scott in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. (It’s in Volume IV). It ends like this:

At the Skelf-hill, the cauldron still

The men of Liddesdale can show;

And on the spot, where they boil’d the pot,

The spreat and the deer-hair ne’er shall grow.

I didn’t have nearly enough fun with Robin Redcap in The Wolf & the Witch, but we’ll see more of him in The Scot & the Sorceress. I think Nyssa knows a lot more about goblins and hauntings than I do—and more than Murdoch would like to believe.