Yesterday, in response to a question from a reader on my ARC team, I added an author’s note to The Masquerade of the Marchioness. If you pre-ordered the book, you’ll probably get the version without the Author’s Note, so you can read it in this blog post.

The question was about the legality of Garrett marrying Penelope, the sister of his dead wife. This is against ecclesiastical law and always has been – marrying the sibling of a dead spouse, or the spouse of a dead sibling (remember Henry VIII) was considered to be consanguinity, even though technically, the couple were not blood relations themselves. It is, however, a tidy solution, when women were more likely to die in childbirth – marrying the dead wife’s sister would provide care for the existing children and some familiarity. The sister couldn’t live respectably in the house of a widower (even her dead sister’s husband) but it was likely that the children already knew her.

There were two hurdles to doing this, however: first, the would-be groom had to find a minister to perform the religious ceremony. Second, the marriage could be challenged by any “interested party” so long as both wife and husband were alive, in which case, it could be annulled or voided. Annulling the match would make their children illegitimate, which could deprive those children from inheriting.

Let’s create an example from Jane Austen’s own work. At one point, Elizabeth says to Jane: “I am determined that only the deepest love will induce me into matrimony. So, I shall end an old maid, and teach your ten children to embroider cushions and play their instruments very ill.” Let’s imagine that Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy never worked out their differences, and this scenario happened instead.

Now, some math. 🙂 If Jane married at 22 – she might have been 23 by the time of the actual marriage, but let’s go with 22 and skew younger – it would take her probably 15 years to have 10 children. It might take closer to 20, but again, we’ll skew younger. So, if she died in childbirth delivering that 10th child, she’d be at least 37. Elizabeth, if unwed, might have come to live with her and Bingley at some point during those 15 years – likely when their father died and Longbourn passed to Mr. Collins. (“Turned out in the hedgerows” as anticipated by Mrs. Bennet, any surviving sisters who were not yet married might also have joined the Bingley household. Alternatively, they and Mrs. Bennett could move in with Mrs. Bennet’s remaining family, either Mrs. Phillips in Meritton or Mr. Gardiner in Gracechurch Street in London. But Elizabeth, certainly, would have gone to Jane and been welcomed.) So, if Jane passed when she was 37, Elizabeth would have been two years younger, 35, and quite unlikely to marry at that point. Mr. Bingley might have married her to provide a maternal influence (and an organizational force) in his household. This purely practical arrangement might have suited both of them well. It might not even have been a consummated match in the end, but it’s a very plausible solution to the dilemma of those ten children being motherless and Bingley, having lost the love of his life, being disinclined to seek another bride who would never hold his heart. He might, quite reasonably, invest his emotional energy in his children by Jane. He might also want to ensure Elizabeth’s financial security as he would be fond of her—if he didn’t make this choice, she would have been looking for somewhere to live, possibly with one of the Gardiner’s children, her nieces and nephews. Remember that Elizabeth’s income after her parents’ death was estimated to be £50 a year, which isn’t much.

There are three well-known examples from the Regency era of men doing this (see my Author’s Note), but there must have been more. The 1835 Marriage Act validates any existing such marriages but forbids them in future. But why was there a marriage act at all?

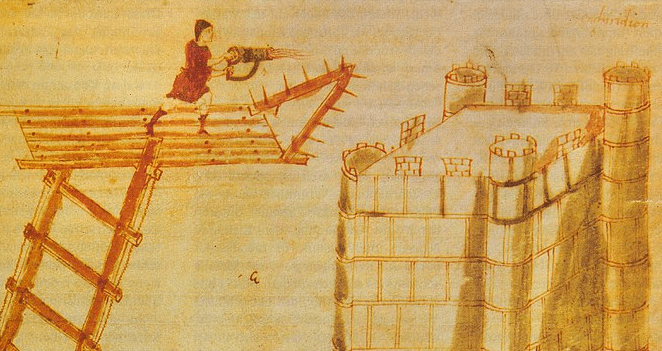

In one of my first medieval history courses at university, one of our assigned books to read was a law code. (It was the Lex Burgundionum from about 500 AD – that’s a Wiki link) Oh, how dull! I think everyone groaned simultaneously in the lecture hall – until the prof pointed out that law codes aren’t so much about what people should do. They are often a response to what people are already doing. So, why did British parliament debate the question of a man marrying his dead wife’s sister? I suggest that it’s because many men were doing it, and those who believed it to be wrong wanted to see the practice stopped. Parlaiment wouldn’t have reviewed and debated a law to address three instances.

The fact remains that Garrett and Penelope could have married. Who could have challenged the match as an interested party? Although this reader suggested that Penelope’s family might do as much, maybe to make trouble, I think this unlikely. If the match was annulled, they would lose all association with the marquis and his father the duke, and thus sacrifice any perks resulting from that connection. The most likely person to challenge the match for personal gain would be Christopher or Anthony, Garrett’s younger brothers, who might wish to take the place of Garrett’s sons in the line of inheritance of the duchy. But Garrett’s sons (his heir and spare) are by Philomena, so their inheritance would be unaffected by the dissolution of his marriage to Penelope. It seems unlikely to me that Christopher or Caroline, given their affection for Garrett and Penelope, would even think of doing this.

So, I don’t see this detail as a challenge to Garrett and Penelope’s HEA, but it is interesting to explore. (You know me – any excuse to dig into the research books!) Thanks to Rebecca for raising the question in the first place. 🙂

Here’s the new Author’s Note at the end of the book:

Author’s Note for The Masquerade of the Marchioness

Could a man marry his dead wife’s sister in the Regency? Technically, he could, although the marriage could be challenged as being within the prohibited degrees i.e. because the couple were too closely related, according to ecclesiastical law. If the marriage was challenged by an interested party, it could be voided or annulled, so long as either husband or wife were still living. This could cast the inheritance of any children into question.

All the same, men did marry the sisters of their dead wives without those matches being challenged. Examples include Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Matthew Boulton and Rear Admiral Charles Austen. Charles was Jane Austen’s brother: he married Frances Palmer in 1807 and Frances’ sister Harriet in 1820 after Frances had died.

Given the nature of Penelope’s blood family, I think it unlikely that they would challenge Penelope’s marriage to Garrett, as that would end their relationship with both the marquis and the duke, and any benefits resulting from that association. Theoretically, Christopher or Anthony could challenge the match in the hope of securing more favor for their own children, but Garrett has an heir and a spare by his first marriage whose claims are beyond dispute. I think we can be confident in Penelope and Garrett’s HEA.

The 1835 Marriage Act made all such existing marriages legal and any subsequent marriages of this type void. It ultimately became legal for a man to marry his dead wife’s sister in 1907, and for a woman to marry her dead husband’s brother in 1921.

My thanks to author Rachel Knowles for her research and blog post on this very subject.